At least this dragged me back into the scene: Kathy Freston's "Shattering the Meat Myth: Humans Are Natural Vegetarians." The piece is, and I hesitate to write this in an age where one's Google News feed bears a striking resemblance to The Onion, a breathtakingly poor scrap of doggerel. Even for ill-researched propaganda, this beast is remarkable in its reckless and wanton distortion of not only science, but of history as well.

This rebuttal in no way touches upon the relative morality or nutrition of diets that include or exclude animal products. In fact, the article came to my attention via Facebook by a respected friend and colleague who takes a valid moral stance against meat consumption. However, with 20,000 other Facebook Likes at the moment, I cannot let the grotesque inaccuracy of the arguments from biology stand. To crib from Samuel L. Jackson's character in Pulp Fiction, "Well, allow me to retort!"

Freston argues as follows (and by all means, read the original to evaluate my summary).

1. The inclusion of meat in the human diet is a product of agricultural civilization (circa 10,000 years ago) and is incompatible with a plant-based biochemistry that dates back "at least tens of millions of years." Prior to the rise of herding, "we may have needed a bit of meat… in times of scarcity."

2. "Humans are herbivores" because we lack physical adaptations that make it easy to tear flesh and hide, such as overdeveloped canine teeth and claws. We resemble the other great apes in that we process food with our hands and must have similarly had "a largely plant-based diet."

3. Humans have "never adapted" to a meat-inclusive diet because meat-eaters have a higher incidence of heart disease, cancer, and diabetes.

Freston's deeply flawed arguments can be attacked from historical, evolutionary, and logical angles. Let's get the observed history out of the way so we can get on to the evo.

A History of Meat Consumption

Let us assume, for the purposes of clarity (since Freston surely provided little), that the "natural" state of humanity refers to traits expressed prior to civilization and its concomitant horrors. Freston has asserted that, before the advent of agriculture-dependent herding 10,000 years ago, humans consumed only small quantities of meat in times of hardship.

Um. But.

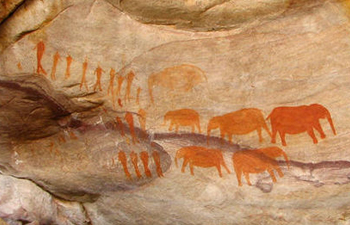

This ignores the physical record of at least 70,000 years of hunting. Hunting big things. From some of the earliest human art on cave walls depicting the hunt, to no shortage of archaeological sites riddled with thousands of mammoth bones (one example), remains of other large and small mammals, deep middens of fish bones and mollusk shells, and so on. By about 10,000 years ago, we were in part responsible for the disappearance of nearly every large mammal in the Western Hemisphere by eating them toward extinction.

South African cave art. Photo Credit San Felszeichnung, from Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, then civilization struck and, well… a grand total of zero of the remotely successful cultures on the planet, now or in recorded history, have categorically excluded meat from their diet. Jared Diamond has a little more to say on the subject.

But let's throw Freston a bone (hah) and examine her argument in the time frame of millions of years. What does biology have to say?

Pretty Much The Same Thing

Freston views humanity through the lens of our closest living relatives, the other great apes, so let's follow. Our sister group, the two chimpanzee species, eat lots of lovely fruits and vegetable bits. Er, and also insects, birds, and mammals including other primates and small relatives of cows and pigs(!). Meat only comprises about 5% of their caloric intake, but for a species relying on its hands, primitive tools and wits, it's seriously impressive that they can muster as much.

Is Freston correct that the human gut tract is like the intestines "of other herbivores" in being very long? No, we're rather intermediate on the spectrum between hypercarnivores and herbivores. Incidentally, carnivore gut tracts are not particularly short "so they can quickly get rid of all that rotting flesh they eat" - another of the bountiful instances in which Freston's sensationalism throws science on the fire. Carnivores have a short and efficient intestinal tract in that they don't need to process large quantities of generally indigestible plant fibers. Our barrel-shaped rib cages, rather than the conical arrangement exhibited by primates that consume more plant matter, in part reflects this reduction in gut length.

Freston laments the absence of wicked claws and fangs (actually, in primates the size of the canine teeth is strongly correlated with social structure rather than with diet) and such. If only humans had a way of compensating for that!

Oh. Right. The whole running and tools thing.

A proper treatment is well beyond the scope of this post, but the evolution of the human body plan from that of a four-footed ancestor appears to have been driven in large part by selective pressure on the ability to run long distances efficiently - and later, while holding tools. Our legs and feet are superbly adapted to long distance running. The NYT has a decent, if brief summary of a few of these characters, and there's a skeletal outline of the endurance running hypothesis over at Wiki. This ability may be nearly 2 million years old, dating back to Homo erectus.

There are a couple reasons for us to run long distances: to poach kills (in fact, that's how we got tapeworms from large cats and hyenas), and to run prey into the ground. Turns out we're pretty good at that (awesome Attenborough video!). We run, we track, and unlike many of our large prey, we can sweat to cool off in the chase. Persistence pays off.

Might meat consumption have put evolutionary pressure on not only our body plans, but on our developmental timing as well? Humans wean their offspring at a very early age relative to other great apes (2 years and change in humans / 5 in chimps / 7 in orangutans, which consume very little animal protein). This is a pattern common to carnivorous mammals (PLoS ONE original). Carnivores wean their offspring faster than do herbivores due to improved milk quality and/or the ability of the offspring to eat high-energy meat. After weaning, females again become receptive to mates; the upshot is that a shorter weaning period increases reproductive capacity.

The preponderance of evidence suggests that Freston's thesis could not be more wrong. The increased means to acquire and utilize meat was likely one of the major driving forces behind the evolution of our bipedal body plan optimized for endurance running, our ability to make and manipulate tools, and our developmental timing. There are other human relatives that were more clearly geared toward eating tough plant matter. They didn't make it.

But It'll Still Kill You

Meat is an extremely efficient source of nutrients, including proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals. When combined with leafy greens and other nutritious foods and an active life style, it helps build healthy bodies. In the short term. In the long term, the consumption of, in particular, red and processed meats is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, and diabetes.

Apparently needing a screamingly ludicrous sound bite from an otherwise distinguished individual, Freston concludes her sad crusade with this gem from Dr. William Roberts, editor of the American Journal of Cardiology. In its entirety: "Although we think we are, and we act as if we are, human beings are not natural carnivores. When we kill animals to eat them, they end up killing us, because their flesh, which contains cholesterol and saturated fat, was never intended for human beings, who are natural herbivores." Coupled with another MD suggesting that "our bodies have never adapted to [eating meat]," it begs the obvious question: why did our ancestors eat meat - and as we have seen above, they certainly did - if it predisposed them to disease? The answer, again, rests in timing.

Except in cases of gross excess and sedentary life styles, these pathologies tend to strike late in life. Specifically, they largely affect post-reproductive (or nearly so) individuals. If you die at 55 from a heart attack but raise ten vigorous, meat-fed offspring, you still have dramatically higher fitness than a vegetarian who lives to 90 but raised five offspring before menopause. Additionally, during the course of human history, "post-reproductive" is a luxury that an incredibly small portion of the population would ever live to see; those disorders would be invisible to natural selection. The MDs' argument is completely vacuous. While they may mean well, I won't stand by to see them misinform the public in order to do so.

It's good to be back.

[Note: Desmond Morris tackled the evolution of humans as a balancing act between carni- and herbivory in his classic The Naked Ape.]